A group of Irish scientists led by an Inishowen researcher have discovered that many huge basking sharks thought to leave Ireland each winter actually remain below the surface of the water around our coast.

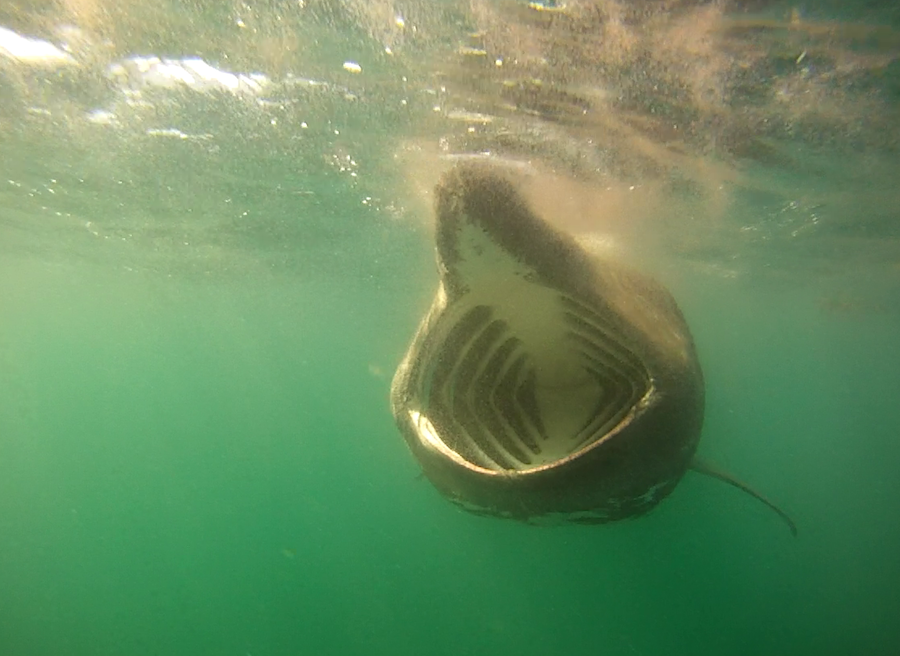

Hundreds of the huge docile creatures visit Irish coastal waters each year and survive on a diet of plankton.

The creatures, which can measure up to 8 metres long and weigh over 5,000 kgs, are often seen momentarily breaking the surface.

Up until recently it was thought that the sharks migrated to warmer waters in places such as Africa in winter.

But now an international research team from Queen’s University Belfast and Western University in Canada have made an amazing discovery that not all sharks are leaving Irish waters.

The findings come from four basking sharks that were equipped with pop-off archival satellite tags off Malin Head.

The tags were placed on the sharks to record water temperature, depth and location over a six-month period.

Research showed that while two of the sharks travelled vast distances to the subtropical and tropical waters off Africa, the other two remained in Irish coastal waters throughout the winter.

First author on the study, Donegal-based Dr Emmett Johnston, said “Our findings challenge the idea of temperature as the main reason for winter dispersal from Ireland.

“Likewise, further evidence of individual basking sharks occupying Irish coastal waters year-round has significant implications for national and European conservation efforts.

“Previously we understood basking sharks departed Irish coastal waters for more southern latitudes in the Autumn in response to falling water temperatures in the north east Atlantic.

This study has very timely implications for Ireland, in that we need to be mindful of year-round residency in the species when designing conservation measures for Irish waters, a process that the Irish Government is in the process of doing right now with new Marine Protected Areas.

“The sharks that remained in our coastal waters over the winter moved away from the surface but remained in relatively shallow waters (60m-100m) on the continental shelf, when compared to the deep waters (400m- 600m or even 1,000m deep) that the sharks that moved into offshore waters occupied.”

Co-author Dr Jonathan Houghton from Queen’s added “This study tempts us to think about basking sharks as an oceanic species that aggregates in coastal hotspots for several months of the year (most likely for reproduction), rather than a coastal species that reluctantly heads out into the ocean when decreasing water temperatures force them to”.

The study was prompted by frequent sightings of aggregating sharks along Ireland’s western coast during summer months.

The team wanted to know whether the seasonal disappearance of sharks from these hotspots in the autumn was driven by changes in water temperature.

The researchers were amazed that sharks off the coast of Africa experienced colder temperatures on a daily basis than the sharks that resided in Ireland; suggesting they didn’t move south simply to find warmer conditions.

The cooler temperatures experienced off Africa resulted from the sharks diving each day to depths of up to 600m, most likely in search of prey.

This deep foraging behaviour began once the individuals moved into Irish offshore waters demonstrating that such habitats should be considered alongside coastal hotspots in future conservation efforts.

With a view to the future, Dr Paul Mensink from Western University said “Our findings highlight the need to understand the role of deep, offshore foraging habitats for a species so commonly sighted just a few metres from our shores”.

The research team are still collaborating on basking sharks as part of the major EU SeaMonitor due to end in early 2023.

With partners from across Ireland, Northern Ireland, Scotland, Canada and the US the project is developing a collective conservation strategy for wide ranging marine species that have inhabited our waters for thousands of years.