REGARDLESS of how the CCCC occasionally surprise us in regard venue choice, with Ballybofey or Omagh unlikely to host an All-Ireland semi-final in this or any foreseeable lifetime, this is a big as it gets – or will ever get – in the north-west, writes Alan Foley

Donegal and Tyrone, with Monaghan’s occasional sprinkling, is the rivalry that has dominated the Ulster SFC since the turn of the decade. It’s an All-Ireland quarter-final without the asterix of the possibility of extra-time. Tyrone’s superior scoring difference means a draw will do.

Getting that is tough at MacCumhaill Park, a ground where they’ve not won in the championship in 45 years and against Donegal, who’ve not been overturned on their own patch in 21 games, since 2010.

On the field, it was Tyrone who began the modern era with intensity and three All-Irelands, leaving Donegal’s ‘tracksuit ravers’ as Eamon McGee termed them, firmly in the shade. Off the field, planty happened too.

“We knew they were fond of the drink and every time we played them it was always tight – up until the last 15 minutes when we’d blow them away,” Tyrone’s Owen Mulligan said last year. “I genuinely don’t think they believed that they could beat us until Jim McGuinness came along and gave them self-belief, confidence and most importantly a game plan.”

Tyrone were McGuinness’s yardstick, a side to which he made constant reference as Donegal’s players were dogged through the coldest of cold winters, 2010 into 2011.

McGuinness, in Until Victory Always: A Memoir, wrote: “They carried themselves with a real sense of certainty and an attitude that let us know: We are Tyrone … youse are nobody. There was that old Six Counties element … a sense that ‘we’ve seen shit you’ve never seen.’ It all communicated to us that they thought they were tougher and just better.”

Tiny instances turned the tide. The first real test of the McGuinness era and Donegal’s newfound but infantile sturdiness was an Ulster semi-final in June 2011.

Tyrone ran from all angles, manufacturing a four-point advantage by the 25thminute. Donegal were in trouble. After his initial sloppy pass, Anthony Thompson’s desire to scamper 80 yards to block at Stephen O’Neill’s feet as he shot for a goal, which would’ve put Tyrone seven up, showed the new Donegal.

They kept in it and those winters nights of torture broadened their lung capacity. With the teams level, Dermot Molloy scored an injury time goal to seal a 2-6 to 0-9 Donegal win.

Donegal won Ulster for the first time in 19 years. In 2012, they defended the crown on their way to an All-Ireland victory and were provincial champions for the third time in four years in 2014. Tyrone, in the meantime, won nothing and were beaten by Donegal four times in the championship in succession.

That made Rory Gallagher’s Donegal favourites for the 2016 Ulster final, where you could’ve fried an egg on the bonnet of a car in Clones.

At ground level at St Tiernach’s Park, there was cool calculation. Donegal were eager not to get caught by one of Tyrone’s lightening counters, so kept possession and kicked first half points from distance. Just 13 seconds into the second half, Patrick McBrearty made it 0-8 to 0-4 for Donegal. But then they stopped.

The statistician clocking up the handpasses would’ve been left with blisters on his fingers. On Twitter, Paul Galvin described the contest as “diahorrea”. Tyrone decided to just throw the kitchen sink and late on, Sean Cavanagh levelled it.

Peter Harte’s monster in the fifth minute of injury time titled the balance of power that afternoon – and for the guts of two years that followed – Tyrone’s way in a 0-13 to 0-11 win. Tyrone’s supporters spilled onto the pitch, a scene so different to their muted Ulster victory of 2010.

“Absolutely the best,” Mickey Harte said that day. “This is the best of all of them because of the famine that was there for six years and because of what had gone before when maybe Ulster titles were taken for granted . This is different, the county was waiting on this.”

Donegal’s run of six Ulster finals in succession also soon came to an end. The following June, just last year, they were hammered 1-21 to 1-12 by Tyrone in the last four in Ulster. It was the beginning of the end for Gallagher.

Tyrone won Ulster with the highest ever scoring average, 1-20, only to see that record broken this year by a rejuvenated Donegal, who managed 2-19 under Declan Bonner as the Anglo-Celt returned to the Hills for the first time in four years. Swings and roundabouts.

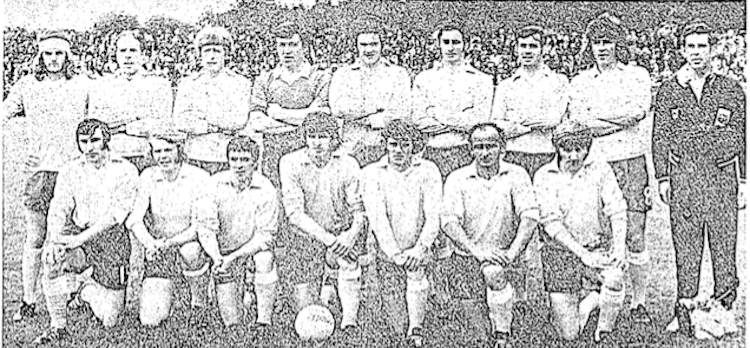

Tomorrow, Donegal and Tyrone stand inches apart again and nobody’s quite sure how to call it. In 1973, the ‘Battle of Ballybofey’ saw Donegal’s Neilly Gallagher left with a bust eye and needing seven stitches by Mickey Joe Forbes.

Substitutes couldn’t warm up amid a flurry of bottles and stones from the terraces as Ballybofey went into lockdown after Tyrone’s 0-12 to 1-7 win. Trouble continued onto the neighbouring town of Castlefin. Donegal threatened to pull the plug.

“As a result of their experiences in recent cross-border games in general and last Sunday’s deplorable scenes in particular, Donegal GAA may seek to leave Ulster and affiliate with Connacht,” read the Donegal Democrat’sfront page, although the same newspaper also said “the scenes afterwards, amongst the Donegal team and its supporters, were to say the least, a disgrace.”

A year later, Donegal decided to tog out Ballybofey before travelling to Omagh to take on Tyrone, returning home afterwards to change.

Problems smouldered to 1989, where Tyrone hammered Donegal 2-13 to 0-7 in an Ulster final replay. Ryan McMenamin recalls those days: “I remember as a wee boy going to the Ulster final in 1989. Clones from my house is maybe an hour’s drive but in 1989, you’d be leaving the house at 10 in the morning because crossing the border meant police and army checkpoints that took two or three hours to go through.

“You weren’t home until 11 at night. People in the south probably didn’t realise what a struggle it was for us to just get playing GAA on the same level as them.”

Whilst Tyrone got their house in order since the arrival of Mickey Harte in 2003 and Donegal under McGuinness eight years later to become two of the powers of the modern game, their recent meetings have been littered by players allegedly getting spat on, a flurry of red cards and for some, it was from where the term sledging was derived.

In Gaelic Games it’s perhaps the truest rivalry and tomorrow between people and teams who see themselves as occasionally similar and sometimes different. And this afternoon, it’s on its biggest stage yet.

Tags: