A stunning documentary on Glenveagh National Park is set to be broadcast on RTE television in the coming weeks.

Glenveagh lies in the heart of the Derryveagh Mountains in the North West of County Donegal and is the second largest of Ireland’s six national parks.

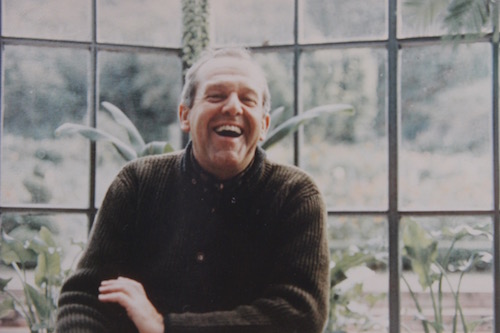

Like so many properties that now belong to the state, Glenveagh Castle was given to the nation by a generous benefactor, and this documentary tells the story of Henry McIlhenny, the last private owner of the Glenveagh estate.

Henry McIlhenny’s grandfather left Donegal in 1843 aged 13 with his young, widowed mother. America offered emigrants the chance to make a completely new life and, in Henry’s grandfather’s case, to create huge wealth by inventing the gas meter.

Less than 100 years after his widowed great-grandmother emigrated to America with four young children, Henry McIlhenny returned to the land of his forebears.

This documentary was shot in Glenveagh and Philadelphia and includes interviews with people who stayed at Glenveagh as Henry’s guests, including American photographer Richard Noble, and with two people who each worked for him for 30 years, his butler Paddy Gallagher and his agent Julian Burkitt. For anyone interested in social history, fine art, the logistics of keeping the castle and deer park running, gardens, interior design and even making a telephone call in the 1970s, this is a fascinating documentary, with stunning photography to match the grandeur and beauty of Glenveagh.

The land which now comprises the National Park was originally consolidated into a single estate in the 19th Century by John George Adair, a wealthy land speculator from County Laois who became notorious for the eviction of 46 families from Derryveagh. Adair built a castle, modelled on Balmoral in Scotland, which was completed in 1873.

In 1929 the estate was bought by another American, Arthur Kingsley Porter, a professor at Harvard who owned the estate for just four years before disappearing mysteriously and his widow sold the estate to a 27 year old American with Ulster Scots roots – Henry McIlhenny.

Henry was in Donegal in September 1939 when Britain declared war on Germany. He returned immediately to the United States where he served with distinction. The documentary contains footage of a kamikaze attack on his ship, the USS Bunker Hill, in May 1945. After the horrors of war, Glenveagh offered peace and sanctuary. For the next 40 years, Henry spent every summer in Donegal.

Around the castle he created gardens that are ranked as some of the finest in Europe, and inside he set about creating a style that was both appropriate and unique.

He was known as a thoughtful and generous host and Glenveagh became renowned for its deer stalking, and amazing food.

Many of the guests who visited Glenveagh reflected Henry’s passion for the arts and some of them liked Donegal so much, they moved there permanently. One such guest was the American photographer Richard Noble, who is interviewed in the documentary. Another was the artist Derek Hill with whom Henry had a friendly rivalry.

In the 1970s, Henry entered into negotiations with the Irish government to sell most of his land, but Glenveagh’s isolation offered no protection against the Troubles. A combination of the Troubles, the expense of keeping the estate going and old age persuaded Henry to leave Glenveagh in 1983. He gave the castle and gardens to the nation, and stipulated that all the people that he had employed would keep their jobs. Glenveagh opened as a National Park in 1984. Henry died in 1986 – he never came back to Ireland.

Philadelphia and Ireland have both benefited greatly from Henry’s generosity, which has ensured that many people can enjoy fabulous works of art, and some of the most spectacular landscapes and gardens in the world.

Narrated by Bibi Baskin, the documentary was written, directed and produced by David Hare (Myrtle Allen: A Life in Food and Ballyfin: Portrait of an Irish Country House).

A look at Glenveagh National Park………

Glenveagh National Park lies in the heart of the Derryveagh Mountains in the north west of County Donegal.

It’s the second largest of Ireland’s six national parks, and like so many properties that now belong to the state, Glenveagh Castle was given to the nation by a generous benefactor.

These benefactors are often completely unknown to the wider public.

The land which is now comprises the National Park, was originally consolidated into a single estate in the 19th Century by John George Adair, a wealthy land speculator from County Laois who became notorious for the eviction of 46 families from Derryveagh.

Adair built a castle, modeled on Balmoral in Scotland, which was completed in 1873.

After he died, his American widow spent much of the next thirty years at Glenveagh, becoming a society hostess, and well-liked in the locality. In 1929 the estate was bought by another American, Arthur Kingsley Porter, a professor at Harvard.

He owned Glenveagh for just four years before disappearing mysteriously, and his widow sold the estate to a 27 year old American with Ulster Scots roots – Henry McIlhenny.

Less than 100 years after his widowed great-grandmother emigrated to America with four young children, Henry McIlhenny returned to the land of his forebears.

The McIlhennys were one of the Ulster Scots families brought over from Scotland as part of the Ulster Plantation. James McIlhenny, Henry’s great grandfather, was a successful cloth merchant in Milford but in 1843 he became seriously ill and on his deathbed he urged his young wife to take their four children to America.

Mary-Anne McIlhenny set sail for America with the children. Her eldest child, John, was just 13 when the family arrived in Philadelphia. They stayed in the city for a few years before moving to Columbus, Georgia, where John studied to become an engineer. He was the mayor of Columbus for 20 years following the American Civil War, and he created the McIlhenny fortune by inventing the gas meter. (Note to editors: the family money did not come from Tabasco Sauce.)

The Ulster Scots in America were known for their philanthropy, and for their belief in good works as a way of giving back to society. One of the many worthy causes supported by Henry’s father was the Philadelphia Museum of Art, where Henry became a curator in 1934, and to which he donated his own extraordinary art collection which included works by Renoir, Van Gogh, Cezanne, Degas, Davide, Landseer, Matisse and Toulouse-Lautrec.

In 1929, aged 19, Henry McIlhenny went to Harvard, to study fine arts. His ambition was to work at a museum, and to become a collector.

While studying at Harvard, Henry had met Arthur Kingsley Porter, the scholar of French medieval art who had bought Glenveagh in 1929. Four years later, while staying in Donegal, Kingsley Porter mysteriously disappeared while bird watching on Inisboffin. His body was never found, and rumours started, including that he had faked his own death.

On hearing of Kingsley Porter’s death, Henry McIlhenny went to see his widow to pay his respects. She invited Henry to stay in Glenveagh when she went back to Donegal to sort out her dead husband’s estate. He fell in love with Glenveagh, and bought it in 1937, aged 27.

Less than 100 years after his grandfather had left Milford, Co Donegal, aged 13, Henry returned in very different circumstances to the land of his forebears.

Henry was in Donegal in September 1939 when Britain declared war on Germany. He returned immediately to the United States and and served in the US Navy once America joined the war after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour.

He served with distinction in fierce battles in the navy, coming under attack by kamikaze pilots. The documentary contains footage of an attack on his ship, the USS Bunker Hill, in May 1945.

After the horrors of war, about which Henry never spoke, Glenveagh offered peace and sanctuary. For the next 40 years, Henry spent every summer in Donegal.

Around the castle he created gardens that are ranked as some of the finest in Europe, and inside he set about creating a style that was both appropriate and unique.

He was known as a thoughtful and generous host and Glenveagh became renowned for its deer stalking, and amazing food cooked by local woman Nellie Gallagher.

Entertaining on such a grand scale meant employing a large number staff. Paddy Gallagher first came to work at Glenveagh in 1954, aged 16. He was to become Henry’s butler for more than 30 years in both Donegal and Philadelphia

Many of the guests who visited Glenveagh reflected Henry’s passion for the arts and some of them liked Donegal so much, they moved there permanently. One such was the American photographer Richard Noble, who is interviewed in the documentary. Another was the artist Derek Hill with whom Henry had a friendly rivalry.

In the 1970s, Henry entered into negotiations with the Irish government to sell most of his land, the first step towards creating a national park. The state acquired 29,000 acres for a modest price, and took on the responsibility of employing the estate workers. Henry retained the Castle and garden, and continued to employ the domestic staff and gardeners.

But at the same time as the negotiations between Henry and the Irish Government were going on, the IRA was intensifying its violent activities. Glenveagh’s isolation offered no protection against the Troubles. A combination of the Troubles, the expense of keeping the estate going and old age persuaded Henry to leave Glenveagh in 1983. He gave the castle and gardens to the nation, and stipulated that all the people that he had employed would keep their jobs. Glenveagh opened as a National Park in 1984. Henry died in 1986 – he never came back to Ireland.

Henry McIlhenny’s grandfather had left Donegal in 1843 aged 13. America offered emigrants the chance to make a completely new life and, in Henry’s grandfather’s case, to create huge wealth. The Ulster Scots tradition of giving back to society through good works and philanthropy was something the McIlhenny family believed in.

Philadelphia and Ireland have benefited greatly from Henry’s generosity, which has ensured that many people can enjoy fabulous works of art, and some of the most spectacular landscapes and gardens in the world.

Many of Ireland’s treasures have been donated to the state by generous benefactors, and this documentary is a small contribution towards giving these men and women the recognition they deserve, but rarely receive.

The documentary was shot in Glenveagh and Philadelphia and includes interviews with people who stayed at Glenveagh as Henry’s guests, and with two people who each worked for him for 30 years, his butler Paddy Gallagher and his agent Julian Burkitt. For anyone interested in social history, fine art, the logistics of keeping the castle and deer park running, gardens, interior design and even making a telephone call in the 1970s, this is a fascinating documentary, with stunning photography to match the grandeur and beauty of Glenveagh.

Henry McIlhenny: Master of Glenveagh will be broadcast on Thursday 23rd March 2017 on

RTÉ One at 10.15pm.